Heritage conservation and the triple bottom line

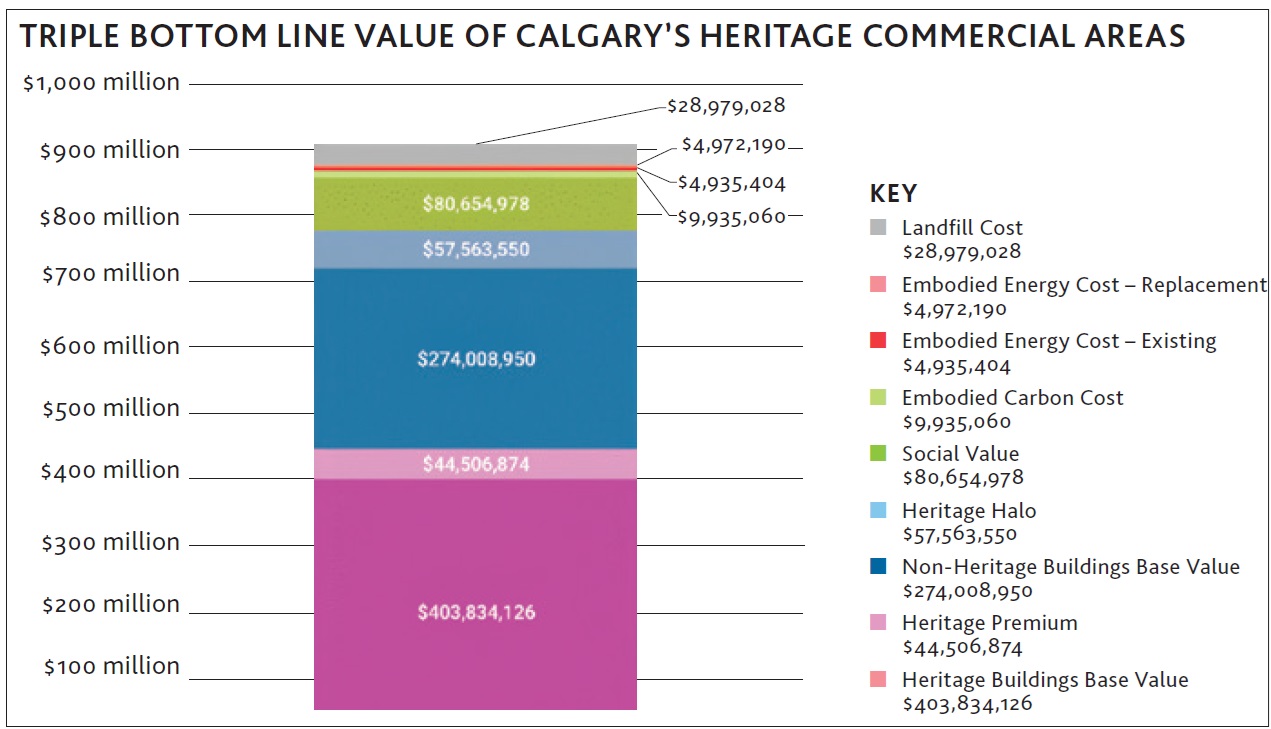

Triple bottom line value of Calgary’s heritage commercial areas.

Contents |

Introduction

Calgary, Alberta, Canada might not come immediately to mind as a city at the cutting edge of heritage conservation policy. Although a very young city in European terms, it is approaching 150 years since its founding. It is a western provincial capital with a population of 1.3 million and is the centre of Canada’s oil and gas industry. While fossil fuel production remains critical to the economy, it is transitioning to other energy sources including major wind and solar facilities. There are six world heritage sites in the province, although all are in the natural heritage category.

But Calgarians also pride themselves on being part of a ‘lifestyle city’, with a growing number of creative industries and an increasing reputation as a culinary capital. Calgary is a city with its eye firmly on the future.

One manifestation of that perspective is the integration of the ‘triple bottom line’ (TBL) into their municipal governance. Nearly 20 years ago, Calgary recognised that to advance the council’s vision to ‘create and sustain a vibrant, healthy, safe and caring community’ it made sense to embed the triple bottom line approach into corporate policies, performance measures, actions and implementation procedures, and to support decision making.

What is the triple bottom line approach?

There is growing recognition for the idea that corporations should not only measure and report their financial results but also their environmental and social impacts: people, planet, profit. First proposed in 1994 by the English writer and consultant John Elkington in the Harvard Business Review, the approach was modelled on the UN’s sustainable development framework: social responsibility, environmental responsibility and economic responsibility.

Since then, hundreds of corporations around the world have adopted some form of the triple bottom line approach, but in local government fewer authorities have seen the logic of incorporating the TBL into their budgeting and policy decision processes: Calgary is one of the exceptions. The city’s Heritage Planning Department wanted an evaluation and monetisation of all three of the TBL elements in four of the city’s commercial areas. Each of these business districts had a concentration of heritage buildings.

As a result of a competitive process, a team assembled by the Canadian architectural firm Lemay was chosen for the assignment. The team consisted of Lemay, one local and one national real estate firm and the American consulting firm, Heritage Strategies International (HSI). Lemay had the primary responsibility for calculating the environmental value while HSI did the economic and social value estimates. The two real estate firms provided extensive data on the local real estate market. The assignment was a particularly challenging one in that no example was found worldwide where a city had calculated a triple bottom line monetised value of its heritage resources.

The environmental value was based on assigning dollar amounts to four measurable costs: 1) embodied energy in the existing building; 2) landfill costs of demolition materials; 3) embodied energy in the construction of a replacement building; and 4) the cost of embodied carbon. A typical building in one of the districts was chosen as a representative example of heritage buildings. The calculation of each of the four measures was made for the case study building. The per square foot cost was then applied to all of the heritage buildings in the four commercial districts.

Based on this approach, the environmental value of the heritage buildings was calculated to be a total of nearly $49 million. This was composed of approximately 20 per cent in embodied energy for the existing and replacement buildings, 60 per cent in landfill costs and 20 per cent in embodied carbon costs.

The social value was estimated based on a ‘willingness to pay’ approach. Willingness to pay (WTP) is a survey-based analytic approach that asks a defined group what the maximum price is that he or she is willing to pay for a product or service. In this case the survey base was an email list maintained by the City of Calgary to communicate public business and information to citizens. The survey resulted in 178 responses from a cross section of the Calgary population. There were several questions in the survey, but the WTP question was worded as follows: ‘How much, if anything, would you be willing to contribute as a voluntary, one-time donation to maintain the historic character and quality of each of these commercial neighbourhoods?’ Since the survey link was distributed by the city, it was important for the survey taker to know that this was not some disguised justification just to raise taxes. So ‘voluntary’ and ‘onetime donation’ were important phrases.

While around a third of respondents said they were unwilling to pay anything, two-thirds were willing to make a voluntary contribution of between $1 and $500. It is important to note that this WTP approach indicates the social value of these areas to those who are unlikely to be direct beneficiaries of the economic values of the area. The sum of the willingness to pay responses, applied to the overall population of Calgary, indicated a social value of between $75 and $87 million dollars, or more than $60 for each person living in Calgary.

The survey included a handful of other questions including one that asked, ‘In choosing a commercial district to visit, how important is each of these variables?’. Sixteen variables were given, each with the following options: very important, somewhat important, neutral and not important. Variables included proximity to work, ease of parking, feeling of public safety, and others. The choice that rated highest was ‘walkable’ followed by ‘historic character of the area’. Although this was a separate question to the willingness to pay question, the high importance attached to historic character reinforced the credibility of the willingness to pay amounts.

Of the three TBL values, the economic value is the one most commonly used with most familiar methodologies. In this instance, the base economic value was established by using the ‘full and true’ estimates generated by the local real estate tax authorities. These numbers were recognised as a reasonable proxy for the market value of the properties. But just using the tax assessor’s value number did not tell the whole story. The Altus Group, a prominent international real estate research company, conducted a linear regression analysis on transactions in the heritage districts. Altus concluded that the marketplace was paying a premium of more than $36 per square foot for heritage properties. Across the heritage buildings this meant an additional value of around $44 million which was termed the ‘heritage premium’. But an even more significant finding by Altus was that non-heritage buildings benefited by their proximity to heritage buildings. This amount, called the ‘heritage halo effect’, added an additional $57 million to the value of non-heritage buildings in the four commercial districts.

So, the triple bottom line value of these four commercial districts ended up being more than $900 million, composed as follows: base economic value of heritage buildings – $404 million; base economic value of non-heritage buildings – $274 million; heritage premium – $44.5 million; heritage halo – $57.5 million; social value – $80.5 million; environmental value – $49 million. In other words, there was a triple bottom line value of a third more than just the base economic value.

What are the lessons from this analysis?

The study raises several key issues of relevance to historic urban areas generally, in Europe as well as North America. 1) Buildings can command a premium from the marketplace when they are heritage structures. 2) Non-heritage buildings can command a premium because of their proximity to heritage buildings. 3) There is a social value to heritage buildings beyond their economic value. 4) There is a measurable environmental value to heritage.

While the methodologies necessary for this triple bottom line valuation can be complex, this study demonstrated that they can be both robust and meaningful and demonstrate an overall value of heritage that has heretofore not been commonly measured.

The outcome of this study was that the City of Calgary is adopting a series of incentives for heritage conservation, funded in part by the enhanced value (and resulting enhanced tax collections) that the triple bottom line approach monetised.

This article originally appeared in the Institute of Historic Building Conservation’s (IHBC’s) 2024 Yearbook. It was written by Donovan Rypkema, the President of Heritage Strategies International (hs-intl.com), a real estate and economic development-consulting firm based in Washington, DC.

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

Related articles on Designing Buildings Conservation.

IHBC NewsBlog

SAVE celebrates 50 years of campaigning 1975-2025

SAVE Britain’s Heritage has announced events across the country to celebrate bringing new life to remarkable buildings.

IHBC Annual School 2025 - Shrewsbury 12-14 June

Themed Heritage in Context – Value: Plan: Change, join in-person or online.

200th Anniversary Celebration of the Modern Railway Planned

The Stockton & Darlington Railway opened on September 27, 1825.

Competence Framework Launched for Sustainability in the Built Environment

The Construction Industry Council (CIC) and the Edge have jointly published the framework.

Historic England Launches Wellbeing Strategy for Heritage

Whether through visiting, volunteering, learning or creative practice, engaging with heritage can strengthen confidence, resilience, hope and social connections.

National Trust for Canada’s Review of 2024

Great Saves & Worst Losses Highlighted

IHBC's SelfStarter Website Undergoes Refresh

New updates and resources for emerging conservation professionals.

‘Behind the Scenes’ podcast on St. Pauls Cathedral Published

Experience the inside track on one of the world’s best known places of worship and visitor attractions.

National Audit Office (NAO) says Government building maintenance backlog is at least £49 billion

The public spending watchdog will need to consider the best way to manage its assets to bring property condition to a satisfactory level.

IHBC Publishes C182 focused on Heating and Ventilation

The latest issue of Context explores sustainable heating for listed buildings and more.